The Tucson Festival of Books is hands down one the best things about Tucson, and it just got better. The two day event on the grassy mall of the University of Arizona campus every March draws illustrious authors and publishers from around the country, as well as local and lesser known writers, and features an extensive hands on science education component. But the food has disappointed me in years past. While Tucson favorites, like Beyond Bread, Tucson Tamale Company, and Brushfire BBQ made appearances, I was always – ALWAYS – distraught not to find the one fair food I had missed most back when I lived in DC: frybread. I’m pretty convinced there was no frybread the last four years because I looked hard. But today at long last:

Unfortunately, the wait was 25 minutes and I was supposed to be volunteering at the Mount Lemmon SkyCenter table, promoting the public observing and UA Science SkySchool opportunities. Fortunately, some great friends (Erik and Moira) waited for me and brought me a treat!

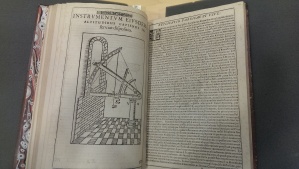

I was especially inspired to see new books being produced because just yesterday I had the opportunity to handle some first editions of historic books that were around 400 years old. The UA/NASA Space Grant invited its interns and graduate fellows on a tour of the library’s rare books in Special Collections, led by Assistant Professor of Astronomy Yancy Shirley. Unbeknownst to most of us, apparently, the University of Arizona has first edition copies of about a dozen of the most important books in the history of astronomy – the Copernicuses, and the Keplers, and the Newtons- remember all of them from your Eurpoean History or History of Science or maybe just your Physics or Calculus class? The ones that fundamentally changed the way we viewed the universe and ours place in it?

Part of the draw was the importance of these books in the history of science, religion, and society. Part of it was the celebrity factor. So what did Galileo Galilei’s handwriting look like? I was able to run my bare fingers over ink on a page said to have been marked by the man himself. Apparently the first edition printing of The Starry Messenger had a typo! So he rounded up all the copies and hand corrected them – much more difficult to do in the age of the internet. It’s kind of a big typo – can you tell in the photos below?

Although his major empirical observations and discoveries were published in Latin texts like this one, Galileo is perhaps equally well known for having explored broader ideas of how the universe operated in a series of thought experiments, as narrated by three characters in a play. He published these not just in Latin, but in Italian so that it was less restricted to the elite – or at least, the elitest of the elite. Remember, in the early 1600’s books were less plentiful and more expensive than today (no Amazon drones to deliver them, either). And literacy rates were lower. So you still had to be fairly elite to read this at all. But still, as someone who thinks about how to connect more people who are not professional scientists to cutting edge discoveries, I am kind of impressed that Galileo wrote this as a play, and that he went to pains to disseminate it to the broader society. He certainly started a conversation (even if, as you may recall, that conversation resulted in his house arrest and excommunication that was only reversed in 1992). I can’t help thinking of modern day Science City sections of the Tucson Festival of Books or Neil deGrasse Tyosn’s resurrection of Carl Sagan’s Cosmos series as the modern day equivalent to Galileo’s Dialogues.

Other books of interest included the Rudolphine Tables, a long term data set begun by Tycho Brahe and eventually published by his student, Johannes Kepler, who realized the implication of their discrepancies in observed orbital positions of planets: namely, that orbits were elliptical instead of perfect circles.

Why were they called the Rudolphine Tables specifically? Why not the Planetary Tables or something more descriptive? In honor of the funder of the observatory, of course! Much like the SkyCenter has the Schulman Telescope and Tumamoc Hill started its legacy of long term ecological research as the Carnegei Desert Laboratory. With decreasing public dollars available for research (budget cuts to National Science Foundation, for example), private investors are once again looming as more important investors in research, which is sparking debate about appropriate funding mechanisms and influence in the direction of research fields. It would be worth looking into the history of private funding, from these observatories in Rennaissance Europe to the Bell Labs, Carnegei, and other industrial development of basic research in the United States in the beginning of the 20th century, to better inform these debates about whether this is a funding model science can safely return to, or whether serious flaws drove the original flight to public infrastructure more than the consolidation and nationalism after WWII. But I digress.

Brahe, of course, published work even before his protege stole the stage. In a very pompous and very unreadable (to me) text in Special Collections, Brahe himself is pictured, looking like he very much enjoys his dinner and enjoys ruffles:

And more puzzlingly, at the end of the text appears a full page ode of some sort. Brahe’s name is at the top, and his funder at the bottom. I wonder whether it is a poem from Brahe dedicated to his sponsors, or vice versa? Is it a form or formalized expression of cooperation, or is this a more lyrical and whimsical expression of the wonder of the universe Brahe felt, that he jotted down between observations, and shared with the reader in order to connect on an artistic as well as technical level?

I think it was also Kepler’s book (the one on the eliptical orbits, published after the Tables) in which I photographed the long division taking up pages and pages. This seemed not atypical of books in this era – unthinkable today, except for a textbook on long division:

Then there was Newton, who you could see drawing curves and exploring ideas with geometry that would later become more unified and more elegantly reproved, as it evolved into what we know as Calculus:

And jumping back to the beginning, before Newton, before Galileo, before Kepler and Brahe, was Copernicus. He waited until he died to publish his conclusion that the earth traveled around the sun, and not vice versa: a revolutionary idea.

Today at the Festival of Books, the SkyCenter sported telescopes allowing attendees to look at the sun safely. It looks so small in the sky that some kids were surprised at the diagrams I handed them at the nearby table, which shows just how tiny we are compared to the sun. But they were not surprised the earth goes around the sun, or that the sun was like other stars in the night sky, just closer. An 8 year old girl asked me whether Pluto had blown up, and that was why it was no longer a planet. I did my best to explain the real reason, that it was still there but we now knew about so many other objects larger than Pluto with similar orbits that we had to either declassify it as a planet, or add about 30 more planets to the list. I tried to imagine what Galileo’s conversations with a strange 8 year old in a public square would have sounded like, and failed.

You can see the books pictured above for yourself in the Special Collections reading room during business hours. Just bring a photo ID and wash your hands.

And go to the Tucson Festival of Books! Help support the academic and informed society culture that produced these discoveries and these giants of innovation, and immortalized them in, well, books.